Author: Hemant Goyat

The Trademarks Registry at New Delhi under the Controller General of Patents, Designs, and Trade Marks (CGPDTM) passed a landmark and historic order of acceptance of a Smell/Olfactory mark, first of its kind in India. The application was filed by Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd., located in Japan, which aimed to seek registration of a small mark. The mark has been described as, “Floral Fragrance/ Smell Reminiscent of Roses as applied to Tyres” under Class 12.

A smell mark is a trademark in which a distinctive scent is used to identify the source of goods or services and distinguish them from others in the market. In simple terms, it is a smell that, when perceived by consumers, immediately connects them to a particular brand.

What was the objection from the Registry?

The Trademarks Registry examined the application and raised objections under Sections 9(1)(a) and 2(1)(zb) of the Trademarks Act, 1999, for lacking distinctiveness and not being supported by a graphical representation, which were mandatory statutory requirements. The Registry questioned whether the mark was capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods from those of others, as required under the Act, and whether it could be clearly and precisely represented on the Trade Marks Register so as to inform the public and competitors of the exact subject matter of protection.

What were the issues during the hearings?

There were issues such as graphical representation, distinctiveness, and scope of protection during the hearings before the Trademarks Registry, which have been discussed as hereunder:

-

Objection on Graphical Representation

The Registry initially objected to the application under Sections 2(1)(zb) and 9(1)(a) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, primarily on the ground that the mark lacked graphical representation.

Since smells are intangible and invisible, the Registry questioned whether the scent could be represented in a manner that was clear, precise, self-contained, and objective.

-

Lack of Distinctiveness

The second major objection related to distinctiveness. The Registry examined whether the smell could truly function as a source identifier, or whether it was merely decorative or descriptive in nature.

-

Scope and Clarity of Protection

The Registry also raised concerns regarding the unclear scope of protection, particularly how the boundaries of a smell mark could be defined and understood by the public and competitors.

Analysis:

The smell marks were not included in the Trademarks Act, 1999. Though, according to section 2(1)(m), “marks include a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours or any combination thereof;”

This definition was considered inclusive, meaning that more categories could be added to it, including smell marks. However, the main issue was the requirement of graphical representation, because a mark cannot be registered unless it can be represented graphically. This created a particular difficulty for smell marks.

To overcome this problem, the applicant with the assistance of professionals from IIIT Allahabad, prepared a graphical representation of the smell mark which attempted to translate a smell into a form that could meet the legal standard.

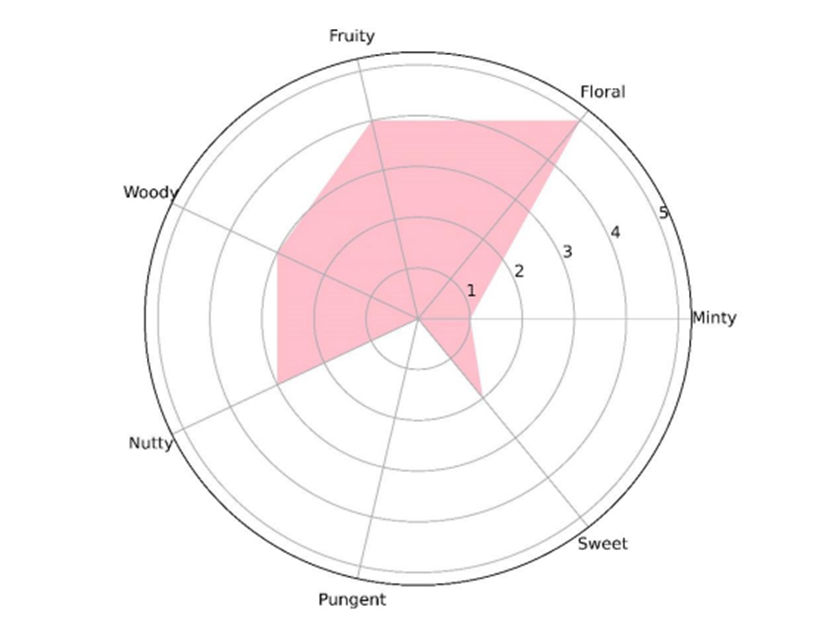

The graph was described as- “A complex mixture of volatile organic compounds released by the petals interact with our olfactory receptors, creating a rose-like smell. Using the technology developed at IIIT Allahabad, this rose-like smell is graphically presented as a vector in the 7-dimensional space wherein each 10 dimension is defined as one of the 7 fundamental smells, namely floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet and minty.”

Order and Outcome:

The CGPDTM concluded that the smell mark satisfied all statutory requirements under the Trade Marks Act, 1999. The application was accepted and directed to be advertised under Section 20 as an “olfactory trademark”, along with its scientific graphical representation and descriptive statement. This marked the first formal acceptance of a smell mark in India.

Impact in India:

Though, this order was the first of its kind in India. Let’s see what can be the impact of this order in India:

-

Expanded Interpretation of Graphical Representation:

One of the biggest hurdles for smell marks worldwide has been the requirement that a trademark must be capable of graphical representation. India’s registry accepted Sumitomo’s innovative seven-dimensional vector chart as sufficient graphical representation. This signals a more flexible, science-inclusive approach to what counts as graphical.

-

Boost for Sensory Branding & Marketing Innovation:

Brands in India now have greater scope to protect sensory features such as smell as part of their brand identity. This enhances possibilities for innovative branding strategies where sensory elements become source identifiers, going beyond traditional logos or names.

-

Recognition of Non-Traditional Marks:

The order confirms that the statutory definition of a trademark in India includes smells as long as they meet legal criteria i.e. distinctiveness and graphical representation. This opens the door for future smell marks and other unconventional marks (like sound marks) to be considered.

-

International Alignment & Influence:

While many other countries like UK have struggled with smell marks due to graphical representation requirements. This order potentially places India at the forefront of adapting global IP law to sensory trademarks. This could influence future developments and encourage applicants to test similar claims internationally.

Conclusion:

The acceptance of Sumitomo’s rose-scent mark marks a turning point in the evolution of Indian trademark law. By recognising an olfactory mark for the first time, the Trademarks Registry has demonstrated a progressive and adaptive approach towards non-traditional trademarks in a rapidly evolving commercial landscape. The order reflects a willingness to move beyond purely visual marks and to acknowledge that brand identity can also be built through sensory experiences such as smell.

At the same time, this decision highlights the growing role of science and technology in intellectual property, particularly in meeting the long-standing requirement of graphical representation. While practical challenges relating to examination, enforcement, and infringement of smell marks remain unresolved, the Sumitomo order undoubtedly opens a new chapter for sensory branding in India. It sets a precedent that is likely to encourage future applications for unconventional marks and stimulate further legal debate on the protection of sensory and other unconventional trademarks.