Authors: Adv Sai Kulkarni & Chintan Kumbharikar

The curious case under the Pakistani Trademark laws has attracted the attention of IP enthusiasts worldwide. This is due to a rather surprising win of a trademark battle by a café in Karachi, against the global coffee tycoon ‘Starbucks’. Café Sattar Baksh has been quite well known due to its coffee and cheeky branding. Launched in 2013, its existence sparked a debate in the public forums given its visual and phonetic semblance since the very beginning.

This blog explores the decision of a Pakistani Court which has ruled in favour of the Sattar Buksh Café raising questions on the Trademark Law.

Parallels with the Indian Case of Sardarbucksh

A Similar case was evoked in the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi wherein a local Delhi coffee joint “Sardarbucksh” was accused of imitating the well-known trademark of the famous Global Coffee Giant Starbucks.

The then logo of Sardarbucksh closely resembled the well-known mark of Starbucks – complete with the matching colour scheme, text placement and even the design. Additionally, it could also be said that the word Sardarbucksh was phonetically similar to that of Starbucks.

After receiving a letter of demand from Starbucks in 2017, Sardarbucksh made some change in their logo. However, that wasn’t enough for the Global Coffee Giant. In 2018, Starbucks sued Sardarbucksh in the Hon’ble Delhi High Court for infringement of their well-known trademark.

The Court emphasized that the assessment of deceptive similarity between trademarks must be made from the perspective of an ordinary person with average intelligence and imperfect recollection. The primary concerns before the Court were the visual similarity of the logos and phonetic resemblance between the marks. Under Indian trademark law, deceptively and phonetically similar marks are not eligible for registration.

If an average consumer is likely to be confused between two brands, the marks may be considered deceptively similar. In this case, the Court observed that a person of ordinary prudence could easily be misled by the similarity between the two names. Consequently, the Court directed the defendants to change their brand name from ‘Sardarbuksh’ to ‘Sardarji-Buksh’ for all outlets.

When Courts Differ: A Look at Sattar Buksh

The Sattar Buksh café opened in Karachi, Pakistan, in 2013, by Rizwan Ahmed and Adnan Yousuf. A local, relatable, and humorous brand. The cafe’s initial logo visually resembled to the Starbucks siren, albeit modified whereby the siren was replaced with a man with a Mustache. The twisted moustache in the logo reminded people of the famous Punjabi saying “mooch nai tey kuch nai” (without moustache, you are nothing). Sattar Buksh had a green circular logo, maintaining a similar design in terms of wavy lines and the circular band. This visual identity strategy achieved immediate recognition through widespread social media virality, leveraging the association with Starbucks while incorporating local cultural elements. The cafe’s menu blended international coffee offerings with local foods, creating a hybrid identity that simultaneously alluded to and differentiated itself from its multinational inspiration.

Due to the similarity of the trademarks – both visually and phonetically, the global coffee giant struck again with a suit of infringement of trademark – this time in a court of Karachi.

The argument of Starbucks centred upon the fact that their brand is a well-known mark globally and therefore is entitled to priority and greater protection. On the other hand, the defence relied upon the fact that, they wish to present parody and humour, and stated that their mark carries a very different meaning, which is “Sattar”, i.e. one of the 99 names of Allah as espoused in Quran. They also cited the 500 years of associated history with this name and ultimately won the Legal battle in the Court of Law.

Although legally Sattar Bukh won the trademark battle, they voluntarily changed some portions of their Logo Mark to minimise further legal trouble.

Comparative Viewpoint:

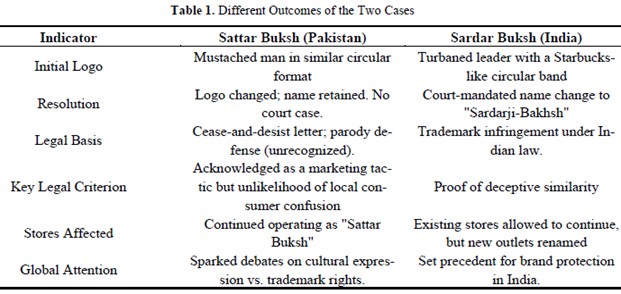

In her paper “Sattar Buksh Cafe vs Starbucks Coffee Trademark Dispute of Pakistan (Sept., 2025)[1]” Samina Yakoob lays down an excellent comparison of the two cases:

[1] Sattar Buksh Cafe vs Starbucks Coffee Trademark Dispute of Pakistan https://www.researchgate.net/publication/

395290502_Sattar_Buksh_Cafe_vs_Starbucks_Coffee_Trademark_Dispute_of_Pakistan

Yakoob perfectly highlights the stark different legal outcomes in the cases of Sattar Buksh in Pakistan and Sardar Buksh in India, both of which involved brands accused of mimicking the globally recognized Starbucks identity.

While Sattar Buksh avoided litigation and retained its name following a cease-and-desist letter, India’s Sardar Buksh faced a court-ordered name change on the grounds of trademark infringement.

A key distinction lies in the legal rationale: Pakistan’s case rested on the unrecognized argument of parody and lack of consumer confusion, while the Indian court applied a more rigid standard of “deceptive similarity” under its trademark law, leading to formal judicial intervention.

The differences in outcomes also reflect broader legal and cultural environments. Pakistan’s more lenient approach, possibly influenced by considerations of local marketing tactics and cultural parody, allowed Sattar Buksh to maintain brand continuity.

In contrast, the Indian judiciary prioritized consumer protection and brand integrity, establishing a precedent for stricter enforcement of trademark rights. Notably, Sardar Buksh was only permitted to retain its original name for existing outlets, underscoring the seriousness with which Indian courts treat potential infringement.

Meanwhile, the Sattar Buksh case sparked international discourse on the tension between cultural expression and intellectual property enforcement, while Sardar Buksh became a benchmark ruling for brand protection in India.

Conclusion

The contrasting outcomes in the Sattar Buksh and Sardar Buksh cases underscore a significant divergence in the enforcement and interpretation of trademark laws across jurisdictions. While the Indian judiciary adopted a stringent approach, reinforcing the standard of deceptive similarity to safeguard consumer interests and brand integrity, the Pakistani handling of Sattar Buksh appears to have sidestepped critical legal scrutiny. The ruling, or rather the lack of a formal judicial determination in Pakistan, has raised serious and pressing questions of law.

How can a deceptively and phonetically similar mark be exempted from legal consequences under Pakistani law? Can a religiously loaded term serve as a valid trademark? Moreover, given that parody is not formally recognized as a legal defence in Pakistan, on what grounds was the Sattar Buksh brand allowed to continue operating? These contradictions not only question the internal coherence of Pakistani trademark jurisprudence but also highlight its apparent departure from global trademark norms. Additionally, international bodies like WIPO must consider facilitating dialogue to ensure that national trademark laws do not undermine the consistency and objectives of global intellectual property protection.

FAQ

1. What is the case of Sattar Buksh vs. Starbucks about?

Answer: The case revolves around the trademark dispute between Sattar Buksh, a coffee shop brand based in the Middle East, and Starbucks, the global coffee chain. Sattar Buksh filed a lawsuit claiming that Starbucks was infringing on its trademark, alleging that Starbucks’ brand name and logo resembled theirs, leading to consumer confusion.

2. Why did Sattar Buksh sue Starbucks?

Answer: Sattar Buksh sued Starbucks because they believed that the American coffee giant’s branding, specifically its name and logo, was too similar to their own. The company argued that this similarity could confuse customers and cause harm to their business, which had built its own identity in the Middle East region.

3. What is the main argument of Starbucks in this case?

Answer: Starbucks countered the lawsuit by arguing that its brand was distinct and had been in the market long before Sattar Buksh gained recognition. Starbucks claimed that there was no likelihood of confusion between the two brands, emphasizing the differences in their operations, locations, and brand identities.

4. What is the significance of this case for trademark law?

Answer: This case is significant for trademark law as it highlights the complexities of brand protection, especially in international markets. It examines the boundaries of what constitutes brand infringement and how similar trademarks can lead to consumer confusion, especially when two companies operate in the same industry or region.

5. Has Sattar Buksh won any part of the case?

Answer: As of now, Sattar Buksh has faced challenges in convincing the courts that there is a clear infringement. The case is ongoing, and while Sattar Buksh has made claims regarding the similarity of the two brands, courts are evaluating whether consumer confusion truly exists.

6. What is the role of geographical location in trademark disputes?

Answer: Geographical location plays a significant role in trademark disputes. In this case, Sattar Buksh operates primarily in the Middle East, while Starbucks is a global brand. The courts have to consider whether the presence of one brand in a particular region creates confusion for consumers or whether Starbucks’ global brand recognition diminishes the likelihood of confusion.