Introduction

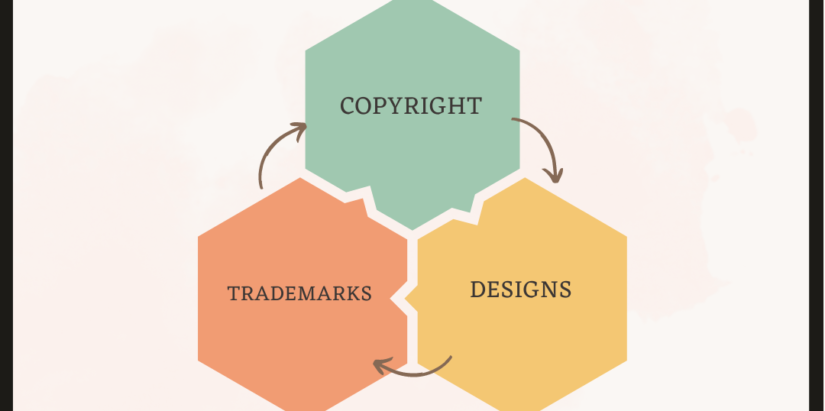

Protecting one’s intellectual property (IP) is essential for both individuals and organisations in today’s fast-paced, creative, and innovative environment. The law governing intellectual property comprises several different types of protection, including copyright, designs, and trademarks. Although each of these three categories of intellectual property protection is used for a unique purpose, there are situations in which they can overlap. In this article, we will investigate how designs, trademarks, and copyright all fall under the umbrella of intellectual property, and we will highlight the significance of each with some real-world instances.

1. Designs

The primary focus of design protection is on the outside appearance or general aesthetics of a product. It protects the one-of-a-kind form, arrangement, pattern, or ornamentation that gives a product its distinctive appearance. Protecting a product’s design helps ensure that its aesthetic qualities are not inappropriately replicated by unauthorised parties.

Example: Design of Apple’s iPhone

The iPhone from Apple is known for having a design that is both iconic and stylish. Several significant design characteristics, including the distinct combination of rounded corners, minimalistic buttons, and the positioning of the home button, are protected by design. Apple’s design rights would be infringed upon by any attempt to copy these design features without the company’s authorization.

2. Trademarks

Trademarks are distinctive signs, symbols, logos, or words that identify and differentiate the source of a product or service. Trademarks protect these distinguishing elements. They act as the identity of a brand and make it possible for customers to recognise and identify products with a particular business.

Example: Coca-Cola’s Logo

The Coca-Cola corporation’s logo is a registered trademark that serves to represent the brand and reputation of the firm. The logo features a unique script and a distinctive shade of red. In order to avoid confusing customers and diluting the value of the brand, the company has taken measures to prohibit other businesses operating in industries comparable to its own from using the logo without permission.

3. Copyrights

The protection afforded by copyright to original works of authorship, whether they be literary, artistic, musical, or theatrical compositions, is known as copyright. It gives the creator the ability to govern how their work is used and grants them exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, exhibit, or perform their work.

Example: the Harry Potter Book Series

The copyright for the Harry Potter books written by J.K. Rowling has been secured. The laws governing copyright apply to not just the written content of the series but also its characters, storylines, and artwork. Rowling is able to maintain complete control over her creative output since this protection stops unauthorised individuals from making copies of the books or distributing them in any way.

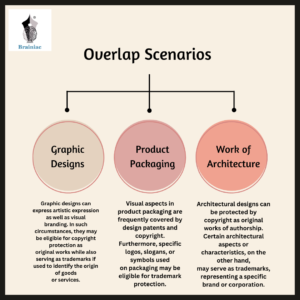

Overlap Scenarios

Graphic Designs – Graphic designs can express artistic expression as well as visual branding. In such circumstances, they may be eligible for copyright protection as original works while also serving as trademarks if used to identify the origin of goods or services.

Example: Nike’s Swoosh

Nike’s distinctive Swoosh emblem is an example of a graphic design that functions as both a trademark and a work protected by copyright. The logo’s distinctive design is protected by copyright as an original artistic creation, while simultaneously serving as a trademark to distinguish Nike’s products.

Product Packaging- Visual aspects in product packaging are frequently covered by design patents and copyright. Furthermore, specific logos, slogans, or symbols used on packaging may be eligible for trademark protection.

Example: Toblerone’s Packaging

Toblerone’s triangle shape, emblem printed on packaging, and distinctive colour combination are all protected by design patents and trademarks. Furthermore, graphical components such as pictures or aesthetic patterns on packaging may be copyrighted.

Works of Architecture: Architectural designs can be protected by copyright as original works of authorship. Certain architectural aspects or characteristics, on the other hand, may serve as trademarks, representing a specific brand or corporation.

Example: the Guggenheim Museum

The distinctive design for the Guggenheim Museum in New York City by Frank Lloyd Wright is not only protected by copyright as an architectural work, but the building’s unique spiral shape and appearance also serve as a trademark for the museum.

Logo Designs: Logo designs frequently embody both creative expression and function as brand identification. As a result, they may be protected as original works by copyright while also being registered as trademarks.

Example: McDonald’s Golden Arches

McDonald’s renowned Golden Arches logo is both protected by copyright and trademark. The design is protected by copyright as an original artistic work, and the logo also acts as a recognisable trademark for the fast-food franchise.

Conclusion

Understanding the overlap of designs, trademarks, and copyright is crucial for individuals and businesses seeking to protect their intellectual property. While designs focus on protecting the aesthetic features of products, trademarks safeguard brand identity, and copyright secures creative works. However, in certain cases, these forms of IP protection can intersect, leading to overlapping rights and complexities. By recognizing these overlaps and seeking appropriate legal counsel, creators and businesses can ensure comprehensive protection for their intellectual property in the evolving landscape of innovation and creativity.